Downshift your time commitments and enjoy more 'life'

Earlier this year, I made a connection with a delightful gentleman by the name of David Frayne.

He was conducting research on one of my favourite subjects, downshifting, and I put him in touch with a few of my contacts.

Following on from my recent piece about the Menmuir family, I thought you might also be interested to read David’s very insightful conclusions from his study.

In the summer of 2008 I did some interviews with downshifters from around the UK in an attempt to gain some insights into alternative views and experiences of work and consumption. This was partly a labour of love but also partly due to the fact that ‘work-life balance’ has become something of a buzzword for the UK government at present. If truth be told, I have felt a little dubious about official interest in the issue.

Firstly I wondered about the terms of the debate. All too often the human soul can be sucked from debates about work, and ‘work-life balance’ offered as a solution to the economic interest in maintaining ‘employee morale’. As the business argument goes, happier workers are, after all, more productive. This aside, what also worried me was the government’s notion that accomplishing a good work-life balance is a simple matter of ‘finding the right rhythm’ in one’s life. This may be true for those attempting to instil minor changes in their working patterns, but means rather less to those who wish to live simply and radically reconsider their life’s priorities.

The truth I inevitably discovered was that the downshifter has to confront problems beyond ‘finding a right rhythm’ and face up to the concrete realities of earning and consuming less. Indeed, each downshifter I interviewed was earning considerably less than they had previously and expressed a deep dread of having to fork out cash for essential expenditures such as bills or school uniforms. Downshifting is financially tricky and for this reason, it takes guts.

This perhaps seems to contradict some of what we know about simple living, namely, that it is about pursuing greater pleasure and peace-of-mind, or that it is about elucidating and asserting one’s priorities to make changes for the better. The central puzzle of simple living for those who do not practice it is then perhaps as follows: how can people possibly be more content in a life in which they are able to earn and consume less than they were before? Is downshifting not experienced as a series of sacrifices? The key to this puzzle resides in the downshifters’ definition of a ‘good life’. One of the main reasons downshifters are able to be happy with less is that they (myself included) seem to live by a definition of the ‘good life’ that does not amount to an ongoing stream of consumer desires. They are therefore able to exist contentedly in a life which an avid worker and consumer might consider meagre.

Furthermore, just because the downshifter voluntarily reduces their income and becomes committed to consuming less, doesn’t mean that they are ascetic or have a compulsion for self-restraint. On the contrary, the downshifters in my study felt the desire to be happy very strongly, and many had come to the realisation that consuming is a very limited means by which to pursue this happiness. Consider that the very survival of consumer capitalism depends on its ability to create needs rather than satisfy them once-and-for-all, and that the good advertiser (at least in the eyes of an ideology of economic growth) is one who successfully promotes dissatisfaction and consumer restlessness. For the downshifters in my study, who had each in their own way confronted these irrationalities, the self-limitation of consumer desires was not a self-denying or abstinent undertaking but rather entailed a certain hedonism.

Shirking off the need to consume lots was linked to a sense of feeling free or having the weight lifted off one’s shoulders. It was one downshifter’s worldview for example, to consider people who aspired to live on the big expensive housing estate near to his house as ‘weird’ or ‘peculiar’. Others celebrated the intrinsic pleasures to be found in food growing, repairing and shopping for bargains.

One can appreciate the virtue of the downshifters’ ability to live happily with less when considering Andre Gorz’s suggestion that capitalism is in an accelerated phase of ‘hyper-obsolescence’. Not only are the things we buy far less durable than they once were, but items once purchased for their functionality - phones, watches, even drinking water - now ebb and flow with the fickle tide of fashion. In other words, because the culture of consumerism attaches a certain symbolic status to the goods we consume, we are ever more likely to see what we own as rubbish and crave something new.

One of the specific virtues in the philosophy of the downshifters in my study was the ability to question the symbolic status which is attached to consumer goods. Consider Alan for example, a primary school teacher who talked in puzzlement about the Dyson vacuum cleaner:

I mean I was in work today with a toddler group and everything was just branded and labelled and y’know, you get the hoover out and it’s like “well it’s not a very good hoover, my Dyson is better”… and well y’know, it’s even down to hoovers now… you’ve gotta have the right hoover! It’s crazy, you know what I mean, this consumerism and commercialisation” (Alan).

Alan’s ability to question the symbolic status of consumer goods such as the branded vacuum cleaner was key in his efforts to live happily with less. He valued items for their durability and functionality and was thus able to stave off feelings of restlessness about the things he owned (indeed, he sold his car without a care). As with the other downshifters I interviewed, Alan’s simple lifestyle wasn’t about self-denial or abstinence then, but about pursuing happiness through freedom from the compulsion to work and consume. If we want to do the same then we must be critical about the path to happiness which consumer culture points us down - it is a path that crumbles beneath our feet and demands we keep moving.

In simple living, one can find a sense of freedom, alternative sources of pleasure, and a psychological alleviation from the cycle of work-and-spend. In this sense - and this is certainly true of the downshifters I interviewed - simple living is far from ascetic. It is borne out of a lust for life and a yearning for more time to appreciate it. To use a phrase by the sociologist, Kate Soper, simple livers are society’s ‘alternative hedonists’, which is perhaps why it was such a pleasure to be interviewing them.

David Frayne

[email protected]

I couldn’t have put it better myself!

I’ll be back with more simple, green stuff tomorrow no doubt.

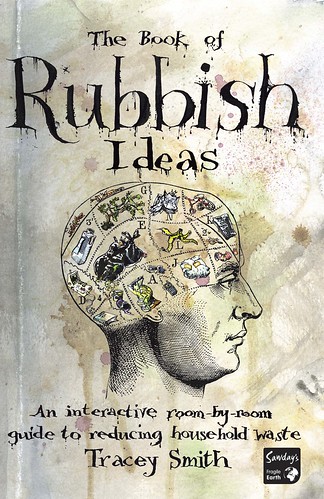

Rubbishly yours,

TSx

Hi - hope you enjoyed my findings. My research is continuing and Tracey invited me to hop on here and tell you a little more about it.

I am a researcher at Cardiff University, completing my doctorate in Sociology.

My work is on the topics of downshifting, voluntary simplicity and people’s experiences around the themes of work and consumption.

If you have reduced your working hours or are involved in the principles of simple living then I would love to hear from you!

Interviews are always relaxed and informal so drop me an email if you want more information or think you might be interested in taking part.

[email protected]

Regards,

David Frayne